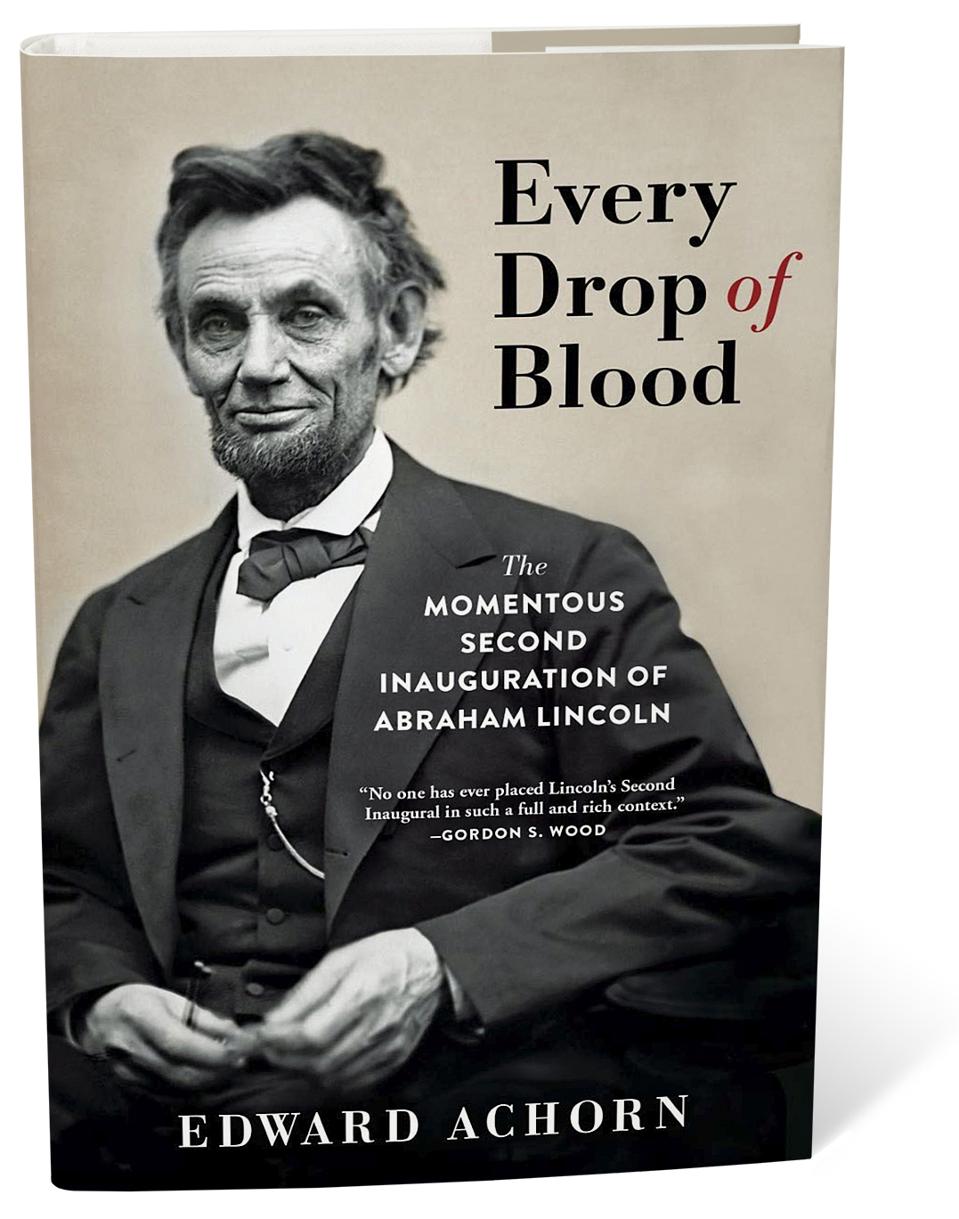

Every Drop of Blood: The Momentous Second Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln—by Edward Achorn (Atlantic Monthly Press, $28). Abraham Lincoln’s

©2015 Stephen Webster

second inaugural address, delivered March 4, 1865, is the finest speech in American history, the only possible exception being his Gettysburg Address. President Lincoln surprised all by not being triumphant over having kept the nation together after a terrible war and by not outlining his postwar policies. No rousing patriotic oration here. Instead, in 700 often harrowing words, Lincoln told the nation that this horrific conflict was God’s punishment for the original sin of slavery and that both North and South were guilty parties:

“Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’ ”

Now was the time for mercy and reconciliation, not hate and vengeance. To Lincoln, the Civil War was one of transcendental importance, a momentous test of whether a nation based on the consent of the governed could endure.

Lincoln was not a churchgoer, and more than once during his life he expressed skepticism about religion. He loved reading the King James Bible, not for reasons of faith but because, as Achorn puts it, “To him it was a practical source of enlightenment, a moving, beautifully written, profoundly wise book, a distillation of millennia of hard-earned human experience about justice, morality and self-advancement. He could quote entire chapters of it by heart.” Yet he had clearly come to believe there was a larger force at work in the world, once telling a general, “Did I not see the hand of God in the crisis—I could not sustain it.”

There has been no shortage of books about this crucial time in American history and about this speech. But Achorn, a noted editor and author, does a splendid job of recreating the atmosphere and experience of being in Washington on the day before and the day of Lincoln’s second inauguration. He has a gift for evocative, elaborate detail, and his descriptions of Washington—from a canal of stinking sewage to the new Capitol dome to the brothels and the various social functions—give readers a full flavor of the good and the plentifully ugly.

Achorn is masterful at sketching known personalities, such as Frederick Douglass, Clara Barton and Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, as well as the lesser known, such as the severely wounded General Selden Connor (who survived to become governor of Maine) and the Reverend John Bachman of South Carolina, who bring the era to life.

Especially moving is Achorn’s portrait of Walt Whitman (whose book of poetry, Leaves of Grass, was hotly controversial; Salmon Chase, the newly minted Chief Justice who would swear in Lincoln for his second term, thought the book obscene). Whitman wrangles an easy clerical job in order to spend immense time on his true mission: tending to wounded and sick soldiers. “On his rounds, Whitman brought with him gifts of candy, fruit, tobacco, stationery, stamped envelopes, newspapers, small amounts of money—all materials the hospitals did not provide. But his greatest gifts were surely his sympathy, his encouragement and his presence.”

The author does a fine job with Lincoln himself.

“Some of the most damaging ordeals any child could suffer—the loss of a mother, abandonment, nights filled with fear, loneliness, filth, cold and hunger—were among Lincoln’s formative experiences. And when he was nineteen, his beloved sister, Sarah, died in the agonies of childbirth. In an 1862 letter to a grieving child, he wrote: ‘In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. . . . I have had experience enough to know what I say.’ ”

Lincoln’s rise in the world was jagged, but all his life experiences had prepared him well for the harsh ordeals of the war, in which disappointments and setbacks were constant. Looking back, one is still astonished at all the obstacles he faced, from incompetent generals to bitter political divisions in the North—and in his own party—not to mention domestic troubles and tragedy.

Achorn’s book is filled with memorable anecdotes, such as General Sherman’s blowing up 23 cannons in Charleston, South Carolina, including the one that fired the first shot at Fort Sumter, which formally began hostilities. Sherman blew up the cannons at the time he figured Lincoln would be taking his second oath of office.

Of course, over everything looms the sinister figure of John Wilkes Booth, a dashing actor. Distinctly interesting in this ugly episode was Booth’s relationship with Lucy Hale, daughter of a prominent political figure: “Strangely, Lucy—who surely had extensive knowledge of Booth’s activities leading up to the tragedy—would be left out of the investigation entirely.”

The contemporary reaction to Lincoln’s speech was all over the map. Lincoln’s own assessment was that the speech would “wear as well as—perhaps better than—any thing I have produced; but I believe it is not immediately popular.”

Stop At Nothing—by Michael Ledwidge (Hanover Square Press, $27). Here’s a book that retired Lieutenant General Mike Flynn, victim of rogue agencies in Washington,

©2015 Stephen Webster

would find grimly satisfying. The rest of us will simply enjoy a fast-paced thriller by an author who has mastered his craft, with lots of action, knowing detail, plenty of twists and turns and characters to cheer or hiss.

Mike Gannon, an American expat and Bahamas-based diving instructor, is out on his boat when he witnesses a Gulfstream crash into the ocean. He can’t call for help because of a radio mishap that occurred when he was trying to haul in the proverbial big fish that got away. Surprised that no rescue planes or boats are coming to the site, he decides to go over the side and dive down to the wreckage. There are no markings on the aircraft, but inside are six dead bodies—and two cases that he brings up only to discover that one is loaded with hundred-dollar bills and uncut diamonds. Gannon’s conclusion: drug runners. He decides to take the loot and hide it in an obscure blue hole—“cave-like water-filled sinkholes that had been formed by eons of rain eroding through the soft Bahamian limestone.” This one has the advantage of an “amazing subway-like network of corridors and caves” that will make discovery by other divers impossible.

But instead of a windfall, Gannon soon learns he has poked an African hornets’ nest of high-powered, highly placed government officials who have all the scruples of ISIS—beheaders with a deadly must-do agenda all their own. Torture, cold-blooded murder, coverups and quick but lethal gun battles abound. Along the way we learn that Gannon has a rather intriguing past of his own, which makes him a formidable foe.

"time" - Google News

August 25, 2020 at 05:00PM

https://ift.tt/2EhQOFA

Two Very Different Books Worth Your Time - Forbes

"time" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3f5iuuC

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Two Very Different Books Worth Your Time - Forbes"

Post a Comment