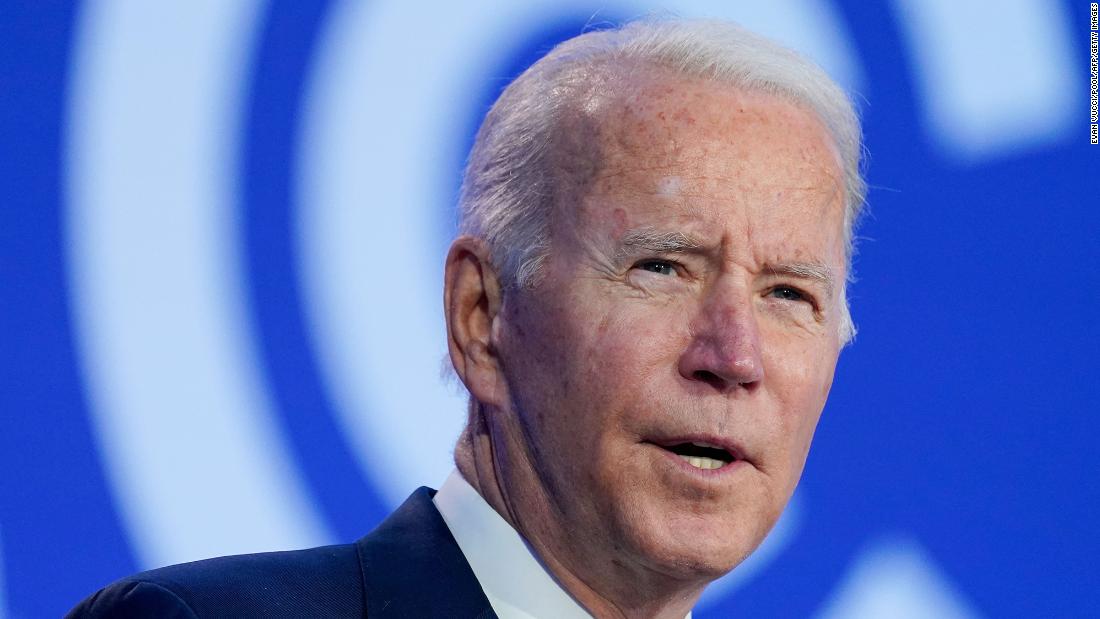

(CNN)From Virginia to New Jersey, Democratic election woes this month had a common thread: the unpopularity of President Joe Biden.

Biden's influence on those states' gubernatorial contests was no surprise. In a nationalized, polarized political era, a president's standing offers the most powerful indicator of his party's prospects.

That makes lifting Biden's approval rating, now mired in the low to mid-40s in many polls, the core challenge for Democrats in next year's midterm elections and then the 2024 presidential race. It won't be easy.

For his first seven months, Biden didn't have a popularity problem. He never enjoyed the 60% levels Barack Obama began with, but he started comfortably above his divisive predecessor, Donald Trump. Replacing Trump's bombast with calm, ramping up coronavirus vaccinations and rushing pandemic relief checks through Congress, the new President steadily drew approval from more than half of Americans.

That changed in midsummer. The unexpected resurgence of the pandemic, the resulting economic slowdown, the chaotic Afghanistan withdrawal and congressional infighting over Biden's economic agenda dragged his standing underwater.

Now the coronavirus has plateaued, job growth has picked up, Afghanistan has fallen from headlines and Congress has passed a major infrastructure bill. It all hasn't boosted Biden's standing yet, but political advisers predict it will in the next few months.

"When the bell rings for the 2022 election season," says his pollster John Anzalone, "things are going to look a lot different than today."

The kinds of voters who've grown disaffected give Biden some hope. Comparing CNN polls from April to November, his largest declines in approval came among Democrats and Democratic-leading independents.

But Democratic inclinations hardly guarantee those voters will swing back in Biden's direction. Regaining the allegiance of former supporters may be tougher than winning them over in the first place; presidential approval ratings fall more easily than they rise.

It's "much harder for circumstances to move them up," observed Daron Shaw, a University of Texas at Austin political scientist who advised the campaigns of former President George W. Bush. "Americans tend to blame politicians for bad times, and credit themselves for good times."

Large swings have grown rarer since polling pioneer George Gallup began asking Americans to rate presidential performance when Franklin D. Roosevelt occupied the White House. Voter realignment has left both parties more ideologically homogenous, rendering poll responses increasingly expressions of partisan identity rather than dispassionate evaluations of the subject at hand.

"Because presidential job approval is more anchored to partisanship, it's gotten to be more difficult to see major fluctuations," said Frank Newport, a senior scientist at the Gallup organization. The last large, rapid rise in presidential approval lifted Bush to 90% following the 9/11 attacks in 2001.

There remains a familiar pattern of presidential decline and gradual recovery, Newport and Gallup colleague Lydia Saad wrote recently in Public Opinion Quarterly. Economic discontent drove down the early standing of Presidents Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama to around where Biden is now; economic recovery revived them for reelection victories.

That's cold comfort to congressional Democrats facing voters in 2022. The Reagan, Clinton and Obama reelections followed punishing midterm defeats.

During the polling era, presidents with job approval of 50% to 60% have lost an average of 12 House seats in midterm elections, Newport and Saad reported. Those below 50% have lost an average of 40 seats.

The most recent CNN Poll of Polls shows Biden averaging 45% approval. Democrats must keep their midterm losses to fewer than five seats to preserve their House majority.

Democratic strategists hope the unique political circumstances of a once-in-a-century pandemic and a violent Capitol insurrection can upend historical patterns. They're less confident that Biden can make it happen on his own.

The White House has launched a communications blitz to tout the job-creating benefits of the infrastructure bill. It plans the same for the Build Back Better climate-change and social safety net legislation if Democrats can unify to pass it.

Yet spiking inflation casts the same shadow over Biden that unemployment cast over Obama in his first year. Though the Great Recession technically ended in June 2009, unemployment kept rising to its peak of 10% four months later.

That obscured nearly anything the new president had to say about the economy -- just as the visceral impact of rising energy and food costs muffles Biden now.

Republicans rode the tea party wave of 2010 to control of the House.

"You can't spin double-digit unemployment," recalled Dan Pfeiffer, Obama's White House communications director at the time. "You can't spin high gas prices and higher grocery prices."

Obama veterans see a different path to accelerating Biden's recovery. Early in their terms, presidents suffer from comparison with their own campaign promises; in reelection years, they benefit from framing sharp contrasts with opposition party challengers.

In the same vein, Democrats hope that the end of intraparty debates over Biden's agenda clears the way for biting attacks on the GOP and Trump, its historically unpopular leader. The fact that some predecessors couldn't claw back to 50% by midterm elections doesn't make it impossible for Biden.

"History's all over the place," Newport concluded. "Only a fool would say, 'Aha, we're now in a brand-new place that will never change.' "

"time" - Google News

November 14, 2021 at 09:06PM

https://ift.tt/3ndlPhi

Can Biden revive his popularity in time for midterm elections? - CNN

"time" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3f5iuuC

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Can Biden revive his popularity in time for midterm elections? - CNN"

Post a Comment